Crazy flute, man!

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Our Home Out West – Cole Escola

loving.

How Drag Influenced ’90s Fashion, from Mugler to Levi’s

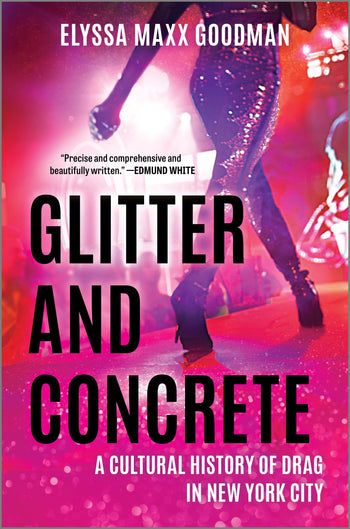

In an excerpt from her new book Glitter and Concrete, author Elyssa Maxx Goodman offers a cultural history of the art form’s groundbreaking impact in New York City FEATURING THE YOUNGER ME.

Source: How Drag Influenced ’90s Fashion, from Mugler to Levi’s

All a dem! Allatwonce!

San Diego fireworks fail. Love it.

Selections Under The Musical Direction of Mr. Paolo DiNola

We gotta get to Rome ASAP, people, capiche? – I’m leaving now – Ciao tutto! Sorry, I’m already gone.

Are you still here? … why?

No, no, bambina. I left. OK? I have other things to do today besides this blog. I have other projects, other gigs…other mixes to find.

I’m working. I’m always working. I’m working right now.

Ciao Paolo!!! Non dimenticare mai ti amo!

Dolly’s Excited

Nordic Voyage 106

A First Few Supermodeling Moments

MORE TO COME. Follow this blog and get an email every time I make a post.

Never Practice But Always Perform

Must-See-T.V.

How else are ya gonna plan ya social schedule? Listen.. without this? Ya got nothin’.

La Prairie (not the skincare line)

The Prairie Look; prairie dress or prairie mess. I wasn’t going to comment on this trend because I thought it would’ve already played out by now. But here we are, and here it is… it’s still hanging around like that last drunk at your party that you can’t get rid of. (oh.. wait. that was me)

Is it new? Is it fresh? Is it reductive? Did Nellie Oleson start designing for Gucci F/W 2020? Would someone please come up with something new to overshadow it? Do I have to do everything? (oh wait.. that’s right.. I never do anything.)

Prairie Mess; Holly Hobbie for Strawberry Shortcake (short cut?) Couture

seen outside the Prada F/W 2022 show in Milan

Who wore it best?

The little Target on the prairie

Diller ’78

Boom

Image

Patricia Routledghe as Victoria Wood

Eugen Sandow- Icon then and now

From music hall to posing pouch, the Victorian strongman (and dreamboat) Eugen Sandow rose to fame as an international celebrity and sex symbol during the close of the nineteenth century.

His stardom even propelled him into the Museum, when in 1901 a cast was made of his naked body and put on display, though it was soon removed and confined to the basement. That was until almost a hundred years later when Arnold Schwarzenegger got in touch.

Modelling his body on the chiselled statues of ancient Greek athletes, Eugen Sandow became an icon for both men and women in Victorian England.

Originally born Friedrich Wilhelm Müller in what was then Prussia, Sandow started off as a circus athlete touring Europe, before arriving in London in 1889. Here he entered a strongman competition, beating the reigning champion and winning instant fame and recognition.

But he also caught the eye of Professor Ray Lankester. In 1901 Lankester was a curator at the British Museum’s South Kensington site, what is now the Natural History Museum.

He saw Sandow’s body as an example of the perfect male form, and had the idea to cast Sandow’s ripped physique to put on display in the Museum. This was met with some criticism, but Lankester was not to be deterred.

‘Firstly it presents a perfect type of a European man,’ Lankester is reported to have said, ‘and secondly, it furnishes a striking demonstration of what can be done in the way of perfecting the muscles by simple means.’ The ‘simple means’ refer to a series of exercise routines trademarked by Sandow and made famous around the world.

In fact, Lankester thought that Sandow could prove to the public that the rippling muscles and pert buttocks as seen on Greek statues that graced many European museums were not just fantasy but attainable to anyone.

But there was another reason for the statue, though reprehensible by modern standards. Lankester planned on commissioning a series of statues that represented the ‘perfect type’ of the different human races. When Sandow’s statue, the first of said series, went on display it was labelled ‘Homo Europiensis’.

Eugen Sandow’s greatest feat of endurance

Lankester commissioned the company Messrs Brucciani & Co of Great Russel Street, London, to make the cast at a cost to the Museum of £55. But this was no typical request.

The plaster itself took at least 15 minutes to harden, meaning the Prussian hunk had to stand motionless in the required pose, without any support, all while tensing his muscles.

Sandow is reported to have said of the experience, ‘This is what had to be done. […] I regard it as the greatest feat of endurance I have ever performed.’

The completed cast was so elaborate it had to be conducted in sections and took an entire month to complete, likely as a result of trial and error.

‘Good heavens, time and time again I thought I’d have given up, the strain was awful,’ Sandow said. ‘I used to finish after each piece was done fairly “blown”, perspiring and winded much more than after the most arduous weight-lifting competition I have ever accomplished.

‘One feels as if one were being suffocated, especially when the mould of the face is being taken. I had to keep the muscles of the chest and abdomen still, and take very small, quick breaths, never entirely filling or emptying the lungs, but just taking in – almost continuously – enough fresh air to take the place of that I used up; at the same time keeping the muscles set so as not to disturb the outer contour.’

Sandow would later remark that while he was proud to have been cast and placed in the Museum, he would not repeat the experience for any amount of money.

An inglorious end for Sandow’s statue

The unveiling of a statue of a burly music-hall celebrity at the then-British Museum on 18 July 1901 was not universally welcomed.

One such detractor is reported to have exclaimed after visiting the statue, ‘What will the Museum be coming to next? A penny show with marionettes and performing dogs, I suppose. They’ve actually got a cast of Sandow the Strong Man – music-hall people in the British Museum, faugh!’

It wasn’t only that some thought that the statue was unsuitable for the serious and professional nature of the Museum – many were apparently of the opinion that the statue was simply not that attractive.

A result of the difficulty in actually making the cast, there were small imperfections where Sandow had struggled to maintain his flexed muscles, while in places the casts were not a perfect fit. This led some to describe it as a ‘monstrosity’.

Of course, Lankester disagreed.

He defended the display in the name of science: ‘Who is to say what are the limits of muscular development – where the line is to be drawn where healthy development leaves off and monstrosity begins?’

However, the bare buttocks and exposed genitalia were too much for the more prudish of Victorians. A fig leaf was cast to cover his manhood, but even this was not enough for some.

Despite the cost, time and effort that went into it, the beefy statue was only on display for three months. It was then relegated to the basement, away from prying (or corruptible) eyes. And there it gathered dust, along with Lankester’s hopes of sculpting a series of perfect human forms.

But the story of Sandow’s strapping statue doesn’t end here. While the statue itself is no longer housed in the Museum, the original life casts are still in the collection.

At some point in the 1990s, a representative of Arnold Schwarzenegger contacted the Museum with a request. As the father of bodybuilding, Sandow was a hero and inspiration to Schwarzenegger – a former bodybuilder himself – who wanted a copy for his own collection.

So in the basement of the Museum, nearly a century after they were first made, the casts were reassembled and recast, before being shipped across the Atlantic.

Sex icon

Sandow was more than just a strongman. Highlights of his illustrious career include opening several Institutes of Physical Culture throughout the UK, being appointed Professor of Physical Culture to King George V, developing training routines for the British army and bringing public awareness of fitness and nutrition through a number of world tours.

He positioned himself as what many consider the first professional bodybuilder, and found ways to further capitalise on his era’s fascination with the human body. Rather than simply continuing to perform on the circuit lifting great weights and entertaining crowds with his feats of strength, Sandow turned to the art of posing.

Using a specially designed posing box, with lights fitted at just the right angle to highlight each of his bulging muscles, he would flex and pose in nothing more than a leopard-skin loincloth.

Undoubtedly there was a sexual element to all this, as he moved from being admired for his performance to being adored for his looks. Sandow even offered private viewings of himself – often naked – once his public performances were over.

But it wasn’t just women who wanted to see his perfect body, as among his followers there were throngs of men.

According to Professor Fae Brauer, who wrote a paper exploring the homoeroticism of the bodybuilder, ‘Sandow implored his male spectators to join him in his dressing-room – as well as those women who could afford US$300 – for the pleasure of feeling his body and fingering his muscles.

‘In Sandow’s dressing room, the two gentlemen attired in dinner suits seem to have feasted their gaze not just upon the pectoral musculature of Sandow’s bared body but also upon his genitalia, with one leaning so far forward that his spectacles have slipped down his nose.’

The sexuality of Sandow has long been debated, but with very little resolution.

He married Blanche Brooks in 1896, with whom he had two daughters named Helen and Lorraine. While there have been rumours that Sandow may have been either gay or bisexual, as is often the case with the history of LGBTQ+ people they have remained just that: rumours.

What we do know is that Sandow and Blanche were on terrible terms by the time of his death in 1925. It is believed that Blanche burned many of his personal letters, before having him buried in an unmarked grave in south London. The cause of this strife will always remain a mystery, as she refused to talk about what occurred between the two of them.

Despite at one point being known from the United States to Australia, Sandow’s name has been partially lost to history outside niche circles. Both performer and entrepreneur, he captured the imagination of entire nations, leaving a legacy in which he sparked a mass interest in exercising for the good of your health while kick-starting the field of professional bodybuilding in the process.

You Played This 27 Times Before!

But that’s only once a year….jeese…can I get a little Christmas moment for myself up in here???? I dont see any of you in a 27 year Ru Paul CHRISTMAS VIDEO. Jus sayin. Go head an play that drum little drummer boy…you do that so sincerely….see that? You see how he playin that with such sincerity? He’s like…rum pah pum BAM!

Sincerely,

Special and unique wishes for each and every one of you individually, this Christmas, really.

I Too Believe These Things

I now accept Liza Minnelli as the one true daughter of Goddess and as my personal savior. As I put on this second hand black sequin jacket, I can honestly say that I feel “Worn Again.” God bless the living memory of Miss Judy Garland and God bless glitter, including all the little beads on all the red pant suits….individually. I promise to do everything with pizzazz from this day forth and to always rehearse responsibly. From the holy trinity of dance, song and drama, entertainment everlasting without end, In Judy’s name we spray, Gaymen.